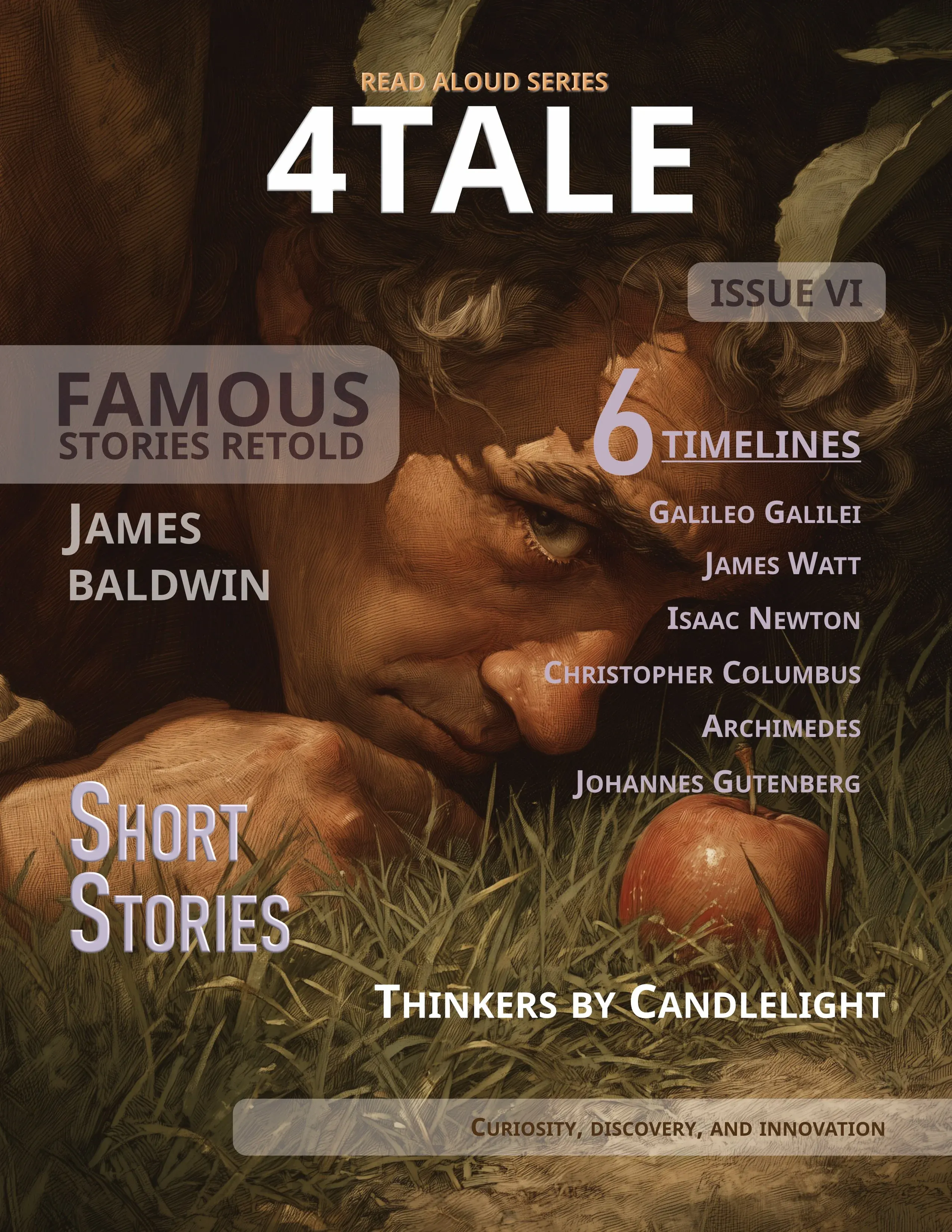

BY JAMES BALDWIN

Galileo and the Lamps

Famous Stories Retold: Story 6 of 50

Heading

Cathedral Observations: At eighteen, Galileo noticed the swinging lamps in Pisa Cathedral, leading to his study of pendulums.

Impact on Timekeeping: His discovery significantly improved the accuracy of timekeeping devices.

A good book we like, we explorers. That is our best amusement, and our best time killer

- Roald Amundsen, Explorer

Galileo's Lamp: The Dawn of Modern Timekeeping

Three centuries ago, a curious mind roamed the streets of Italy, forever questioning the world around him. Galileo, a name now synonymous with ground-breaking scientific advances, was but a young man embarking on a journey of discovery. One evening, while observing the rhythmic sway of lamps in Pisa's cathedral, he stumbled upon a foundational concept of timekeeping. The unassuming dance of these oil lamps sparked a revelation that would forever change our perception of time. By the end of this tale, you will unravel the secrets of time and discover how Galileo's ingenious observations gave birth to the pendulum clock.

The Early Life of Galileo: A Mind of Inquiry

In the heart of Italy, over three hundred years ago, there lived a young man named Galileo. A thinker akin to Archimedes, Galileo was perpetually intrigued by the world around him — constantly questioning, always seeking a deeper understanding. His insatiable curiosity birthed numerous inventions, including rudimentary versions of the microscope, the telescope, and even the thermometer.

Galileo's relentless pursuit of knowledge paved the way for countless scientific breakthroughs. His innovation and creativity were unparalleled, making him one of the most influential figures in the realm of scientific discovery. It was his unique, inquisitive mind that led to the fateful observation in the cathedral of Pisa that would forever change our understanding of time and motion.

A Cathedral in Pisa: The Lamps that Changed History

At the tender age of eighteen, Galileo found himself in the cathedral of Pisa at dusk, just as the lamps were being lit. These lamps, fueled by oil, hung from long rods affixed to the cathedral ceiling. The slightest breeze or touch would set them swinging back and forth like pendulums.

It was a common sight, yet Galileo saw something that millions had overlooked. He noticed a pattern in the swinging lamps — a rhythm, a predictable and consistent cycle. This unassuming observation sparked a trail of thought that would lead to one of the most significant discoveries in the history of timekeeping.

Dive Deeper 'Timeless Wisdom' Podcast

Video with Captions and Visualizer

The Intricate Dance of the Lamps: Observations and Discoveries

Galileo was fascinated by the oscillating lamps. He observed that lamps suspended from rods of equal length swayed back and forth in unison, maintaining identical periods of oscillation. Conversely, lamps on shorter rods swung at a faster pace than their lengthier counterparts.

Intrigued, Galileo began a series of experiments to further investigate this phenomenon. His observations of the lamps had revealed a principle that was then unknown, but would soon become fundamental to the science of mechanics. This principle, which came to be known as the law of the pendulum, would underpin the development of the pendulum clock, forever altering the way we measure time.

Galileo's Room: The Birthplace of Experiments

In the solitude of his room, Galileo pursued his fascination with the swinging lamps. Armed with cords of varying lengths and weights, he sought to replicate the intriguing movements he observed in the cathedral. Each cord was set into motion, mimicking the pendulum-like swings of the lamps. Over time, Galileo noted patterns, linking the length of the cords to the speed of their vibrations. A cord measuring 39 1/10 inches, for instance, vibrated exactly sixty times in a minute. This was a pivotal realization in the history of timekeeping, laying the foundation for further exploration and experimentation.

The Science Behind the Pendulum: Understanding the Mechanics

Galileo's mind was a crucible of scientific inquiry. His experiments with the cords led him to unravel the science behind pendulums. The pivotal discovery was that the length of a pendulum determined the speed of its swing. A shorter cord resulted in faster vibrations, while a longer one led to slower swings. A cord a fourth of the length of the 39 1/10 inches cord vibrated twice as fast, and to make it vibrate three times as fast, the cord had to be a mere ninth of its original length. This principle, once fully understood, could be applied to practical inventions such as clocks.

The Pendulum Clock: The Impact on Modern Timekeeping

The humble beginnings of Galileo's experiments in his room led to an invention that revolutionized the world: the pendulum clock. His studies of the swinging lamps and their replication using cords and weights provided the basis for the development of the pendulum in timekeeping devices. The discovery that the length of a pendulum determines the speed of its swing was the essential principle behind the mechanism of the pendulum clock. This invention drastically improved the accuracy of timekeeping and paved the way for advancements in various fields including navigation, science, and technology. It's a testament to Galileo's enduring legacy, reminding us that even the simplest observations can lead to significant discoveries that change the world.

Conclusion

Galileo's youthful curiosity in the rhythmic sway of lamps, combined with his relentless pursuit of knowledge, paved the way for the invention of the pendulum clock. By meticulously observing and experimenting with the pendulums, he uncovered the secrets of time that have revolutionized modern timekeeping. We owe our perception of time and the precision of our clocks to Galileo's insightful observations that evening in the cathedral of Pisa. As you delve into the intricacies of pendulum science, perhaps you too could make a discovery as monumental as Galileo's.