In the opening chapter of General John B. Gordon's interesting "Reminiscences of the Civil War" he tells us that the bayonet, so far as he knew, was very rarely used in that war, and never effectively. The bayonet, the lineal descendant of the lance and spear of far-past warfare, had done remarkable service in its day, but with the advent of the modern rifle its day ended, except as a weapon useful in repelling cavalry charges or defending hollow squares.

Fearful as their glittering and bristling points appeared when levelled in front of a charging line, bayonets were rarely reddened with the blood of an enemy in the Civil War, and the soldiers of that desperate conflict found them more useful as tools in the rapid throwing up of light earthworks than as weapons for use against their foes.

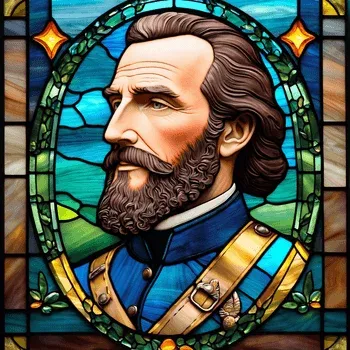

Later in his work Gordon gives a case in point, in his vivid description of a bayonet charge upon the line under his command on the bloody field of Antietam. This is well worth repeating as an illustration of the modern ineffectiveness of the bayonet, and also as a story of thrilling interest in itself.

As related by Gordon, there are few incidents in the war which surpass it in picturesqueness and vitality.

The battle of Antietam was a struggle unsurpassed for its desperate and deadly fierceness in the whole war, the losses, in comparison with the numbers engaged, being the greatest of any battle-field of the conflict. The plain in which it was fought was literally bathed in blood.

It is not our purpose to describe this battle, but simply that portion of it in which General Gordon's troops were engaged. For hour after hour a desperate struggle continued on the left of Lee's lines, in which charge and counter-charge succeeded each other, until the green corn which had waved there looked as if had been showered upon by a rain of blood.

But during those hours of death not a shot had been fired upon the centre. Here General Gordon's men held the most advanced position, and were without a supporting line, their post being one of imminent danger in case of an assault in force.

As the day passed onward the battle on the left at length lulled, both sides glad of an interval of rest. That McClellan's next attempt would be made upon the centre General Lee felt confident, and he rode thither to caution the leaders and bid them to hold their ground at any sacrifice.

A break at that point, he told them, might prove ruinous to the army. He especially charged Gordon to stand stiffly with his men, as his small force would feel the first brunt of the expected assault. Gordon, alike to give hope to Lee and to inspire his own men, said in reply,—

"These men are going to stay here, general, till the sun goes down or victory is won."

Lee's military judgment, as usual, was correct. He had hardly got back to the left of his line when the assault predicted by him came. It was a beautiful and brilliant day, scarcely a cloud mantling the sky. Down the slope opposite marched through the clear sunlight a powerful column of Federal troops.

Crossing the little Antietam Creek they formed in column of assault, four lines deep. Their commander, nobly mounted, placed himself at their right, while the front line came to a "charge bayonets" and the other lines to a "right shoulder shift." In the rear front the band blared out martial music to give inspiration to the men. To the Confederates, looking silently and expectantly on the coming corps, the scene was one of thrilling interest. It might have been one of terror but for their long training in such sights.

Who were these men so spick and span in their fresh blue uniforms, in strange contrast to the ragged and soiled Confederate gray? Every man of them wore white gaiters and neat attire, while the dust and smoke of battle had surely never touched the banners that floated above their heads.

Were they new recruits from some military camp, now first to test their training in actual war? In the sunlight the long line of bayonets gleamed like burnished silver. As if fresh from the parade-ground they advanced with perfect alignment, their steps keeping martial time to the steady beat of the drum. It was a magnificent spectacle as the line advanced, a show of martial beauty which it seemed a shame to destroy by the rude hand of war.

One thing was evident to General Gordon. His opponent proposed to trust to the bayonet and attempt to break through Lee's centre by the sheer weight of his deep charging column. It might be done. Here were four lines of blue marching on the one in gray. How should the charge be met?

By immediate and steady fire, or by withholding his fire till the lines were face to face, and then pouring upon the Federals a blighting storm of lead? Gordon decided on the latter, believing that a sudden and withering burst of deadly hail in the faces of men with empty guns would be more than any troops could stand.

All the horses were sent to the rear and the men were ordered to lie down in the grass, they being told by their officers that the Federals were coming with unloaded guns, trusting to the bayonet, and that not a shot must be heard until the word "Fire!" was given. This would not be until the Federals were close at hand. In the old Revolutionary phrase, they must wait "till they saw the whites of their eyes."

On came the long lines, still as steady and precise in movement as if upon holiday drill. Not a rifle-shot was heard. Neither side had artillery at this point, and no roar of cannon broke the strange silence. The awaiting boys in gray grew eager and impatient and had to be kept in restraint by their officers.

"Wait! wait for the word!" was the admonition. Yet it was hard to lie there while that line of bayonets came closer and closer, until the eagles on the buttons of the blue coats could be seen, and at length the front rank was not twenty yards away.

The time had come. With all the power of his lungs Gordon shouted out the word "Fire!" In an instant there burst from the prostrate line a blinding blaze of light, and a frightful hail of bullets rent through the Federal ranks. Terrible was the effect of that consuming volley. Almost the whole front rank of the foe seemed to go down in a mass. The brave commander and his horse fell in a heap together. In a moment he was on his feet; it was the horse, not the man, that the deadly bullet had found.

In an instant more the recumbent Confederates were on their feet, an appalling yell bursting from their throats as they poured new volleys upon the Federal lines. No troops on earth could have faced that fire without a chance to reply. Their foes bore unloaded guns. Not a bayonet had reached the breast for which it was aimed. The lines recoiled, though in good order for men swept by such a blast of death. Large numbers of them had fallen, yet not a drop of blood had been lost by one of Gordon's men.

The gallant man who led the Federals was not yet satisfied that the bayonet could not break the ranks of his foes. Reforming his men, now in three lines, he led them again with empty guns to the charge. Again they were driven back with heavy loss. With extraordinary persistence he clung to his plan of winning with the bayonet, coming on again and again until four fruitless charges had been made on Gordon's lines, not a man in which had fallen, while the Federal loss had been very heavy.

Not until convinced by this sanguinary evidence that the day of the bayonet was past did he order his men to load and open fire on the hostile lines. It was an experiment in an obsolete method of warfare which had proved disastrous to those engaged in it.

In the remaining hours of that desperate conflict Gordon and his men had another experience to face. The fire from both sides grew furious and deadly, and at nightfall, when the carnage ceased, so many of the soldiers in gray had fallen that, as one of the officers afterward said, he could have walked on the dead bodies of the men from end to end of the line. How true this was Gordon was unable to say, for by this time he was himself a wreck, fairly riddled with bullets.

As he tells us, his previous record was remarkably reversed in this fight, and we cannot better close our story than with a description of his new experience. He had hitherto seemed almost to bear a charmed life. While numbers had fallen by his side in battle, and his own clothing had been often pierced and torn by balls and fragments of shells, he had not lost a drop of blood, and his men looked upon him as one destined by fate not to be killed in battle.

"They can't hit him;" "He's as safe in one place as another," form a type of the expressions used by them, and Gordon grew to have much the same faith in his destiny, as he passed through battle after battle unharmed.

At Antietam the record was decidedly broken. The first volley from the Federal troops sent a bullet whirling through the calf of his right leg. Soon after another ball went through the same leg, at a higher point. As no bone was broken, he was still able to walk along the line and encourage his men to bear the deadly fire which was sweeping their lines.

Later in the day a third ball came, this passing through his arm, rending flesh and tendons, but still breaking no bone. Through his shoulder soon came a fourth ball, carrying a wad of clothing into the wound. The men begged their bleeding commander to leave the field, but he would not flinch, though fast growing faint from loss of blood.

Finally came the fifth ball, this time striking him in the face, and passing out, just missing the jugular vein. Falling, he lay unconscious with his face in his cap, into which poured the blood from his wound until it threatened to smother him. It might have done so but for still another ball, which pierced the cap and let out the blood.

When Gordon was borne to the rear he had been so seriously wounded and lost so much blood that his case seemed hopeless. Fortunately for him, his faithful wife had followed him to the war and now became his nurse. As she entered the room, with a look of dismay on seeing him, Gordon, who could scarcely speak from the condition of his face, sought to reassure her with, the faintly articulated words, "Here's your handsome husband; been to an Irish wedding."

It was providential for him that he had this faithful and devoted nurse by his side. Only her earnest and incessant care saved him to join the war again. Day and night she was beside him, and when erysipelas attacked his wounded arm and the doctors told her to paint the arm above the wound three or four times a day with iodine, she obeyed by painting it, as he thought, three or four hundred times a day. "Under God's providence," he says, "I owe my life to her incessant watchfulness night and day, and to her tender nursing through weary weeks and anxious months."