The romance of war dwells largely upon the exploits of partisan leaders, men with a roving commission to do business on their own account, and in whose ranks are likely to gather the dare-devils of the army, those who love to come and go as they please, and leave a track of adventure and dismay behind them.

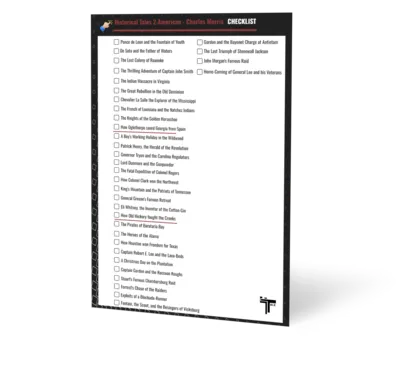

There were such leaders in both armies during the Civil War, and especially in that of the South; and among the most daring and successful of them was General John H. Morgan, whose famous raid through Indiana and Ohio it is our purpose here to describe.

Morgan was a son of the people, not of the aristocratic cavalier class, but was just the man to make his mark in a conflict of this character, being richly supplied by nature with courage, daring, and self-possession in times of peril.

He became a cavalry leader in the regular service, but was given a free foot to control his own movements, and had gathered about him a body of men of his own type, with whom he roamed about with a daring and audacity that made him a terror to the enemy.

Morgan's most famous early exploit was his invasion of Kentucky in 1862, in which he kept the State in a fever of apprehension during most of the summer, defeating all who faced him and venturing so near to Cincinnati that the people of that city grew wild with apprehension.

Only the sharp pursuit of General G C Smith, with a superior cavalry force, saved that rich city from being made an easy prey to Morgan and his men.

As preliminary to our main story, we may give in brief one of Morgan's characteristic exploits. The town of Gallatin, twenty miles north of Nashville, was occupied by a small Federal force and seemed to Morgan to offer a fair field for one of his characteristic raids.

His men were ready,—they always were for an enterprise promising danger and loot,—and they fell on the town with a swoop that quickly made them its masters and its garrison their captives.

While the victors were paying themselves for their risk by spoiling the enemy, Morgan proceeded to the telegraph office, with the hope that he might find important despatches.

So sudden had been the assault that the operator did not know that anything out of the usual had taken place, and took Morgan for a Northern officer. When asked what was going on, he replied,—

"Nothing particular, except that we hear a good deal about the doings of that rebel bandit, Morgan. If he should happen to come across my path, I have pills enough here to satisfy him." He drew his revolver and flourished it bravely in the air.

Morgan turned on the braggart with a look and tone that quite robbed him of his courage, saying, "I am Morgan! You are speaking to Morgan, you miserable wretch. Do you think you have any pills to spare for me?"

The operator almost sank on his knees with terror, while the weapon fell from his nerveless hand.

"Don't be scared," said the general. "I will not hurt you. But I want you to send off this despatch at once to Prentiss."

The much-scared operator quickly ticked off the following message,—

"Mr. Prentiss,—As I learn at this telegraph office that you intend to proceed to Nashville, perhaps you will allow me to escort you there at the head of my troop."

"John Morgan."

What effect this despatch had on Prentiss history sayeth not.

With this preliminary account of Morgan and the character of his exploits, we proceed to the most famous incident of his career, his daring invasion of the North, one of the most stirring and exciting incidents of the war.

The main purpose of this invasion is said to have been to contrive a diversion in favor of General Buckner, who proposed to make a dash across Kentucky and seize Louisville, and afterward, with Morgan's aid, to capture Cincinnati.

It was also intended to form a nucleus for an armed counter-revolution in the Northwest, where the "Knights of the Golden Circle" and the "Sons of Liberty," associations in sympathy with the South, were strong. But with these ulterior purposes we have nothing here to do, our text being the incidents of the raid itself.

General Morgan started on this bold adventure on June 27, 1863, with a force of several thousand mounted men, and with four pieces of artillery. The start was made from Sparta, Tennessee, where the swollen Cumberland was crossed in boats and canoes on the 1st and 2nd of July, the horses, with some difficulty, being made to swim.

After successful encounters with Jacob's cavalry and a troop of Wolford's cavalry, the adventurers pushed on, reaching the stockade at Green River Bridge on July 4.

Here Colonel Moore was strongly intrenched with a small body of Michigan troops, and sent the following reply to Morgan's demand for a surrender: "If it was any other day I might consider the demand, but the 4th of July is a bad day to talk about surrender, and I must therefore decline."

Moore proved quite capable, with the aid of his intrenchments, of making good his refusal, Morgan being repulsed, after a brisk engagement, with a loss of about sixty men, as estimated by Captain Cunningham, an officer of his staff.

Lebanon was taken, after a severe engagement, on the 5th, yielding the Confederates a good supply of guns and ammunition, and the Ohio was reached, at Brandenburg, in a drenching rain, on the evening of the 7th. Here two steamers were seized and the whole force crossed on the next day to the Indiana shore.

General Morgan's force had been swelled, by recruits gained in Kentucky, until it now numbered four thousand six hundred men, and its four guns had become ten. But he was being hotly pursued by General Hobson, who had hastily got on his track with a cavalry force stronger than his own.

This reached the river to see the last of Morgan's men safe on the Indiana shore, and one of the steamers they had used floating, a mass of flames, down the stream.

Hobson's loss of time in crossing the stream gave Morgan twenty-four hours' advance, which he diligently improved. The advance of Rosecrans against Bragg had prevented the proposed movement of Buckner to the north, and there remained for Morgan only an indefinite movement through the Northern States with the secondary hope of finding aid and sympathy there.

It was likely to be an enterprise of the utmost peril, with Hobson hotly on his track, and the home-guards rising in his front, but the dauntless Morgan did not hesitate in his desperate adventure.

The first check was at Corydon, where a force of militia had gathered. But these were quickly overpowered, the town was forced to yield its quota of spoil, three hundred fresh horses were seized, and Morgan adopted a shrewd system of collecting cash contributions from the well-to-do, demanding one thousand dollars from the owner of each mill and factory as a condition of saving their property from the flames.

It may be said here that Corydon was the principal place in which any strong opposition was made by the people, the militia being concentrated at the large towns, which Morgan took care to avoid, pursuing his way through the panic-stricken villages and rural districts. There were other brushes with the home-guards, but none of much importance.

The failure of the original purpose of the movement, and the brisk pursuit of the Federal cavalry, left Morgan little to hope for but to get in safety across the Ohio again. In addition to Hobson's cavalry force, General Judah's division was in active motion to intercept him, and the whole line of the Ohio swarmed with foes.

The position of the raiders grew daily more desperate, but they rode gallantly on, trusting the result to destiny and the edge of their good swords.

On swept Morgan and his men; on rushed Hobson and his troopers. But the former rode on fresh horses; the latter followed on jaded steeds. For five miles on each side of his line of march Morgan swept the country clear of horses, leaving his own weary beasts in their stead, while Hobson's force, finding no remounts, grew steadily less in number from the exhaustion of his horses.

The people, through fear, even fed and watered the horses of Morgan's men with the greatest promptness, thus adding to the celerity of his movements.

Some anecdotes of the famous ride may here be fitly given. At one point on his ride through Indiana Morgan left the line of march with three hundred and fifty of his men to visit a small town, the main body marching on. Dashing into the place, he found a body of some three hundred home-guards, each with a good horse.

They were dismounted and their horses tied to the fences. Their captain, a confiding individual, on the wrong side of sixty, looked with surprise at this irruption, and asked,—

"Whose company is this?"

"Wolford's cavalry," was the reply.

"What? Kentucky boys? Glad to see you. Where's Wolford?"

"There he sits," answered the man, pointing to Morgan, who was carelessly seated sideways on his horse. Walking up to Wolford,—as he thought him,—the Indiana captain saluted him,—

"Captain, how are you?"

"Bully; how are you? What are you going to do with all these men and horses?"

"Why, you see that horse-thieving John Morgan is in this part of the country, cutting up the deuce. Between you and me, captain, if he comes this way, we'll try and give him the best we've got in the shop."

"You'll find him hard to catch. We've been after him for fourteen days and can't see him at all," said Morgan.

"If our hosses would only stand fire we'd be all right."

"They won't stand, eh?"

"Not for shucks. I say, captain, I'd think it a favor if you and your men would put your saddles on our hosses, and give our lads a little idea of a cavalry drill. They say you're prime at that."

"Why, certainly; anything to accommodate. I think we can show you some useful evolutions."

Little time was lost in changing the saddles from the tired to the fresh horses, the hoosier boys aiding in the work, and soon the Confederates, delighted with the exchange, were in their saddles and ready for the word. Morgan rode up and down the column, then moved to the front, took off his hat, and said,—

"All right now, captain. If you and your men will form a double line along the road and watch us, we will try to show you a movement you have never seen."

The captain gave the necessary order to his men, who drew up in line.

"Are you ready?" asked Morgan.

"All right, Wolford."

"Forward!" shouted Morgan, and the column shot ahead at a rattling pace, soon leaving nothing in sight but a cloud of dust. When the news became whispered among the astonished hoosiers that the polite visitor was Morgan instead of Wolford, there was gnashing of teeth in that town, despite the fact that each man had been left a horse in exchange for his own.

As Morgan rode on he continued his polite method of levying a tax from the mill-owners instead of burning their property. At Salem, the next place after leaving Corydon, he collected three thousand dollars from three mill-owners. Capturing, at another time, Washington De Pauw, a man of large wealth, he said to him,—

"Sir, do you consider your flour-mill worth two thousand dollars?"

De Pauw thought it was worth that.

"Very well; you can save it for that much money."

De Pauw promptly paid the cash.

"Now," said Morgan, "do you think your woollen-mill worth three thousand dollars?"

"Yes," said De Pauw, with more hesitation.

"You can buy it from us for that sum."

The three thousand dollars was paid over less willingly, and the mill-owner was heartily glad that he had no other mills to redeem.

Another threat to burn did not meet with as much success. Colonel Craven, of Ripley, who was taken prisoner, talked in so caustic a tone that Morgan asked where the colonel livd.

"At Osgood," was the answer.

"That little town on the railroad?"

"Yes," said the colonel.

"All right; I shall send a detachment there to burn the town."

"Burn and be hanged!" said the colonel; "it isn't much of a town, anyhow."

Morgan laughed heartily at the answer.

"I like the way you talk, old fellow," he said, "and I guess your town can stand."

As the ride went on Morgan had more and more cause for alarm. Hobson was hanging like a burr on his rear, rarely more than half a day's march behind—the lack of fresh horses kept him from getting nearer. Judah was on his flank, and had many of his men patrolling the Ohio.

The governors had called for troops, and the country was rising on all sides. The Ohio was now the barrier between him and safety, and Morgan rode thither at top speed, striking the river on the 19th at Buffington Ford, above Pomeroy, in Ohio. For the past week, as Cunningham says, "every hill-side contained an enemy and every ravine a blockade, and we reached the river dispirited and worn down."

At the river, instead of safety, imminent peril was found. Hundreds of Judah's men were on the stream in gunboats to head him off. Hobson, Wolford, and other cavalry leaders were closing in from behind. The raiders seemed environed by enemies, and sharp encounters began.

Judah struck them heavily in flank. Hobson assailed them in the rear, and, hemmed in on three sides and unable to break through the environing lines, five hundred of the raiders, under Dick Morgan and Ward, were forced to surrender.

"Seeing that the enemy had every advantage of position," says Cunningham, "an overwhelming force of infantry and cavalry, and that we were becoming completely environed in the meshes of the net set for us, the command was ordered to move up the river at double-quick, ... and we moved rapidly off the field, leaving three companies of dismounted men, and perhaps two hundred sick and wounded, in the enemy's possession.

Our cannon were undoubtedly captured at the river."

Morgan now followed the line of the stream, keeping behind the hills out of reach of the gunboat fire, till Bealville, fourteen miles above, was reached.

Here he rode to the stream, having distanced the gunboats, and with threats demanded aid from the people in crossing. Flats and scows were furnished for only about three hundred of the men, who managed to cross before the gunboats appeared in sight. Others sought to cross by swimming. In this effort Cunningham had the following experience:

"My poor mare being too weak to carry me, turned over and commenced going down; encumbered by clothes, sabre, and pistols, I made but poor progress in the turbid stream. But the recollections of home, of a bright-eyed maiden in the sunny South, and an inherent love of life, actuated me to continue swimming....

But I hear something behind me snorting! I feel it passing! Thank God, I am saved! A riderless horse dashes by; I grasp his tail; onward he bears me, and the shore is reached!" And thus Cunningham passes out of the story.

The remainder of the force fled inland, hotly pursued, fighting a little, burning bridges, and being at length brought to bay, surrounded by foes, and forced to surrender, except a small party with Morgan still at their head. Escape for these seemed hopeless.

For six days more they rode onward, in a desperate effort to reach the Ohio at some unguarded point. They were sharply pursued, and, at length, on Sunday, July 26, found themselves very hotly pressed. Along one road dashed Morgan, at the full speed of his mounts.

Over a road at right angles rushed Major Rue, thundering along. It was a sharp burst for the intersection. Morgan reached it first, and Rue thought he had escaped. But the major knew the country like a book. His horses were fresh and Morgan's were jaded. Another tremendous dash was made for the Beaver Creek road, and this the major reached a little ahead.

It was all up now with the famous raid. Morgan's men were too few to break through the intercepting force. He made the bluff of sending a flag with a demand to surrender; but Rue couldn't see it in that light, and a few minutes afterward Morgan rode up to him, saying, "You have beat me this time," and expressing himself as gratified that a Kentuckian was his captor.

A mere fragment of the command remained, the others having been scattered and picked up at various points, and thus ended the career, in capture or death, of nearly all the more than four thousand bold raiders who had crossed the Ohio three weeks before. They had gained fame, but with captivity as its goal.

Morgan and several of his officers were taken to Columbus, the capital of Ohio, and were there confined in felon cells in the penitentiary. Four months afterward the leader and six of his captains escaped and made their way in safety to the Confederate lines. Here is the story in outline of how they got free from durance vile.

Two small knives served them for tools, with which they dug through the floors of their cells, composed of cement and nine inches of brickwork, and in this way reached an air-chamber below. They had now only to dig through the soft earth under the foundation walls of the penitentiary and open a passage into the yard.

They had furnished themselves with a strong rope, made of their bed-clothes, and with this they scaled the walls. In some way they had procured citizen's clothes, so that those who afterward saw them had no suspicion.

In the cell Morgan left the following note: "Cell No. 20. November 20, 1863. Commencement, November 4, 1863. Conclusion, November 20, 1863. Number of hours of labor per day, three. Tools, two small knives. La patience est amère, mais son fruit est doux [Patience is bitter, but its fruit is sweet]. By order of my six honorable confederates."

Morgan and Captain Hines went immediately to the railroad station (at one o'clock in the morning) and boarded a train going towards Cincinnati. When near this city, they went to the rear car, slackened the speed by putting on the brake, and jumped off, making their way to the Ohio. Here they induced a boy to row them across, and soon found shelter with friends in Kentucky.

A reward of one thousand dollars was offered for Morgan, "alive or dead," but the news of the ovation with which he was soon after received in Richmond proved to his careless jailers that he was safely beyond their reach.

A few words will finish the story of Morgan's career. He was soon at the head of a troop again, annoying the enemy immensely in Kentucky.

One of his raiding parties, three hundred strong, actually pushed General Hobson, his former pursuer, into a bend of the Licking River, and captured him with twelve hundred well-armed men.

This was Morgan's last exploit. Soon afterward he, with a portion of his staff, were surrounded when in a house at Greenville by Union troops, and the famous Confederate leader was shot dead while seeking to escape.