BY JAMES BALDWIN

The Gordian Knot

Famous Stories Retold: Story 15 of 30

Heading

Ancient Puzzle: The Gordian Knot was an intricate knot tied by Gordius, the King of Phrygia, and it was said that whoever could untie it would rule Asia.

Historical Impact: The phrase "cutting the Gordian Knot" has come to represent a bold solution to a complicated problem.

A good book we like, we explorers. That is our best amusement, and our best time killer

- Roald Amundsen, Explorer

Solving the Gordian Knot: Phrygia's Ancient Riddle

Jump into the heart of ancient Phrygia in this exploration of the Gordian Knot, a fascinating tale that continues to captivate audiences centuries later. Its significance extends beyond the historical and cultural, serving as a compelling metaphor in modern times. Prepare to journey back through time as we unravel the mysteries of the Gordian Knot, examining its profound implications and the powerful legacy it has left behind. By the end of this journey, you will have a deeper understanding of this intriguing tale and its enduring relevance in today's world.

The Prosperous Land of Phrygia and its Descent into Chaos

In the western part of Asia, there once lay a rich and beautiful region known as Phrygia. This land was prosperous, bountiful, and home to a people who were related to the Greeks. The Phrygians, as they were known, were a happy and well-to-do society. Their landscape was generously blessed with gold mines, fine marble quarries, fruitful vineyards, and olive orchards. They were known for the high-quality wool they produced from their flocks of sheep.

However, tranquility did not last forever. As the society grew wiser, individuals began to prioritize their own interests over those of the community. The gold miners would partake in the fruits of the valley dwellers, the vine growers would kill the sheep of the hill dwellers, and the shepherds would steal the gold of the mountaineers. This lead to a war that filled the once prosperous and happy land with distress and sorrow. The descent into chaos had begun.

The Intervention of the Oracle and the Arrival of Gordius

Amidst the turmoil, the wise men of the land decided to consult the oracle of Apollo. They hoped that the divine wisdom would guide them out of their misery. A messenger was sent to the oracle, and upon his return, he brought a cryptic message, "In lowly wagon riding, see the king who'll peace to your unhappy country bring."

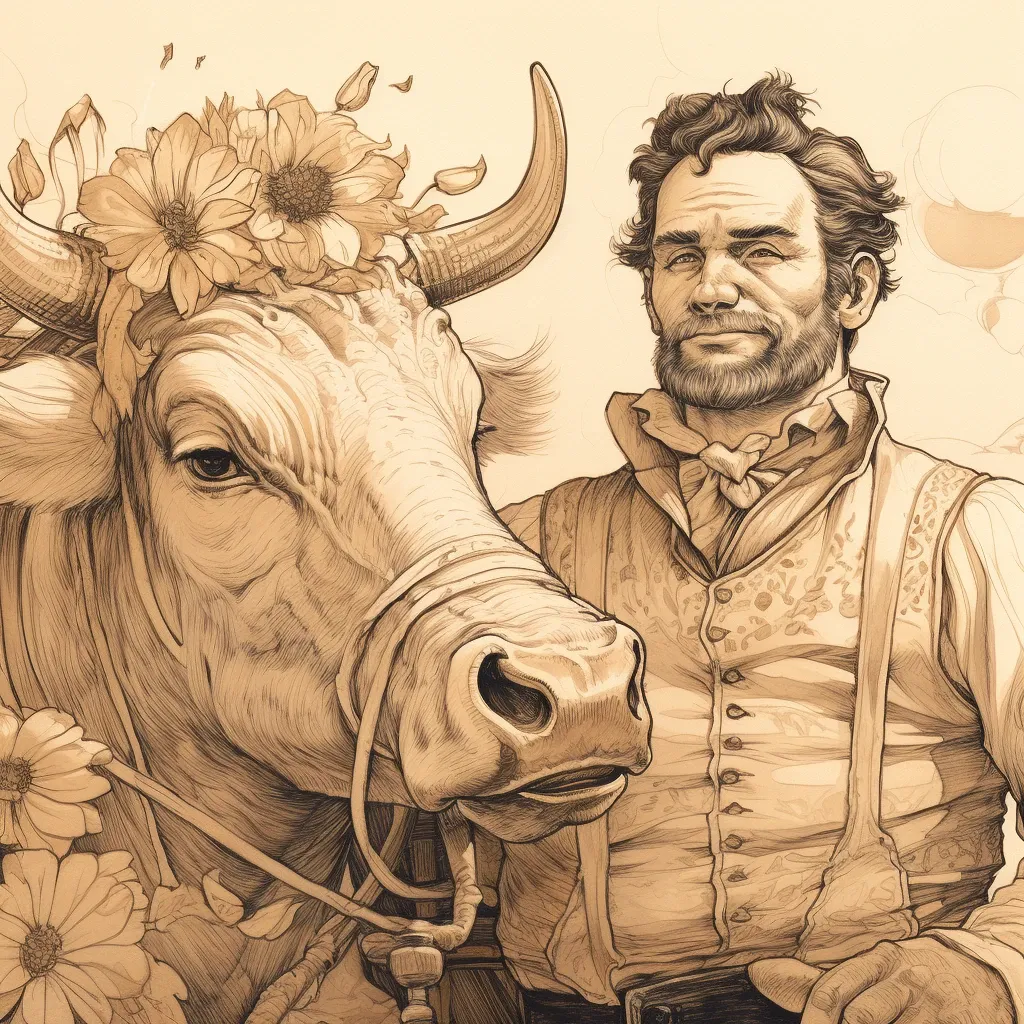

While the meaning of this message puzzled the people, a humble peasant named Gordius, known to be the most hard working man in all of Phrygia, rode into town on his ox-wagon with his wife and child. Suddenly, one of the wise men declared Gordius to be the king prophesied by the oracle. The crowd, in agreement, hailed Gordius as their king, marking the arrival of a new era.

Dive Deeper 'Timeless Wisdom' Podcast

Video with Captions and Visualizer

Gordius' Ascension to Kingship and the Creation of The Gordian Knot

Gordius accepted his newfound role, promising to do his best as a king. He drove straight to the temple of Jupiter to offer thanks and sacrifices. Here, he made a peculiar offering - his wagon. Gordius took the ox yoke and fastened it to the wagon pole in such a complex knot that the ends of the rope were hidden and no man could see how to undo it. This knot, later known as the Gordian Knot, was Gordius' gift to the great Being.

With the knot tied and his ascension to kingship complete, Gordius set out to fulfill his duties as king. His humble beginnings and the circumstances of his ascension were the beginnings of a tale that would echo through the corridors of time.

The Peaceful Reign of King Gordius

Following his divine appointment and the sacrificial offering to mighty Jupiter, Gordius took on the mantle of kingship with humble determination. "I don't know much about this business," he conceded, "but I'll do my best." And he did. Being a simple, hard-working man himself, Gordius understood his people and their needs. His reign ushered in an era of peace and prosperity, healing the once strife-ridden land of Phrygia.

King Gordius enacted laws that were fair and just, fostering harmony among his people. The gold miners, vine growers, and shepherds no longer coveted each other's wealth but respected each other's contribution to the kingdom. As a result, the land flourished from the mountains to the plains, restoring the prosperity it had once enjoyed.

The Legend of the Gordian Knot and its Prophecy

King Gordius' legacy extended beyond his peaceful reign. His name is forever linked to the Gordian Knot, a complex knot tied to the yoke of his ox-wagon, and presented as an offering to Jupiter. This intricate knot, whose ends were hidden, baffled all who attempted to untie it, adding a layer of mystery and intrigue to the legend of Gordius.

The oracle of the temple further fueled the legend by prophesying, "Only a very great man could have tied such a knot as that but the man who shall untie it will be much greater." The prophecy suggested that the man who could undo the Gordian Knot would be destined to rule over the entire world, not just Phrygia.

Alexander the Great and the Unraveling of the Gordian Knot

The prophecy lay dormant for several centuries until the arrival of the young and ambitious king from Macedonia, Alexander the Great. Already a conqueror of Greece and victor over the king of Persia, Alexander was drawn to the Gordian Knot and the oracle's prophecy.

Upon seeing the knot, Alexander approached it with his characteristic audacity. Unable to find the ends of the rope, he unsheathed his sword and with a single stroke, he sliced the knot into pieces, causing the yoke to fall to the ground. "It is thus," he declared, "that I cut all Gordian knots."

With this symbolic act, Alexander the Great affirmed his destiny to conquer Asia and his claim to the prophecy, "The world is my kingdom." The legend of the Gordian Knot hence found its resolution in the bold actions of Alexander, intertwining the narratives of the humble King Gordius and the mighty Alexander the Great.

Conclusion

As we conclude our journey through the annals of Phrygian history, we find the timeless tale of the Gordian Knot resonating with us in a peculiar manner. It serves as a potent reminder that sometimes the most convoluted problems can be solved with a decisive act of will, much like how Alexander the Great cut through the knot. This ancient anecdote continues to inspire, teaching us that not all problems require intricate solutions, some simply require courage and audacity. From Phrygia to our present day, the Gordian Knot remains a compelling metaphor for overcoming seemingly insurmountable challenges.