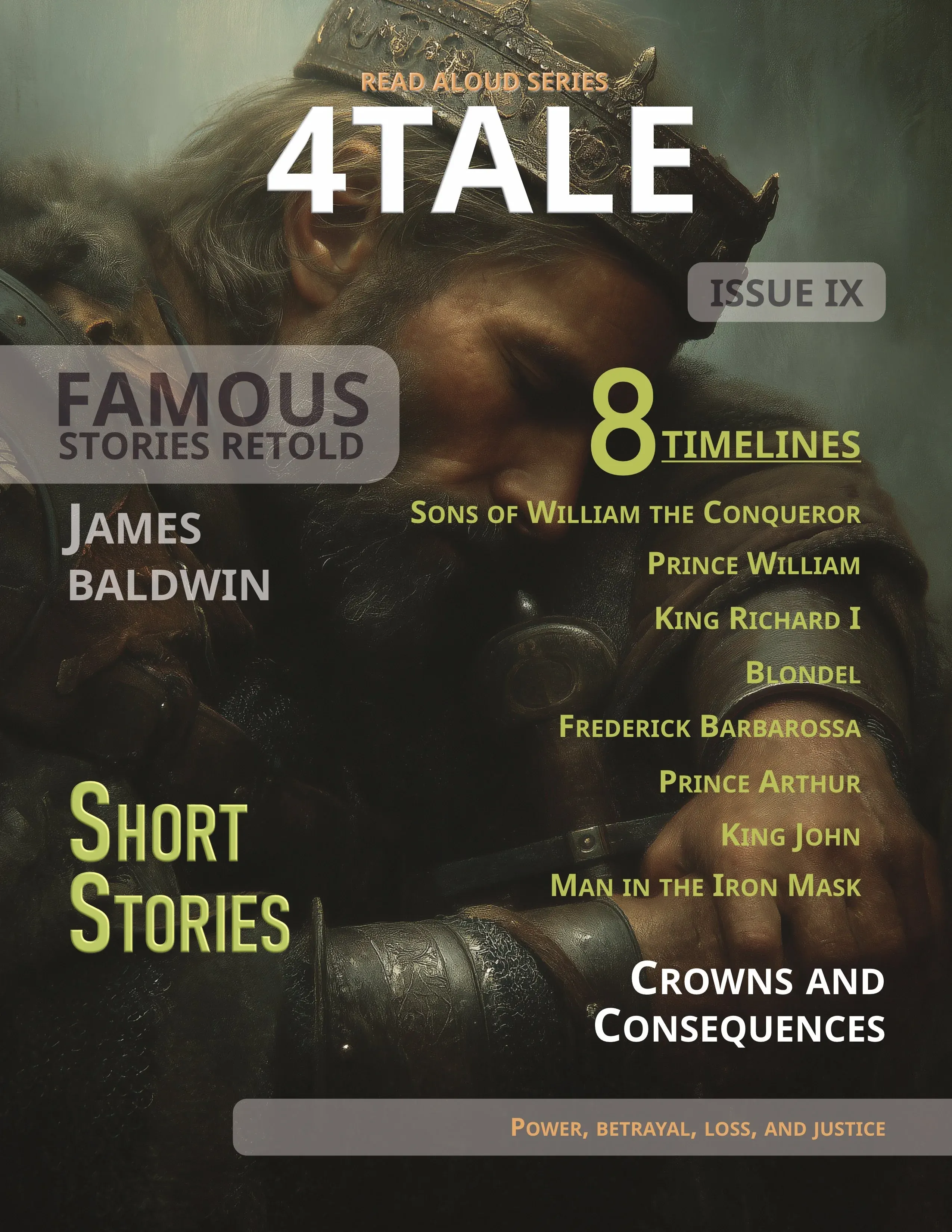

BY JAMES BALDWIN

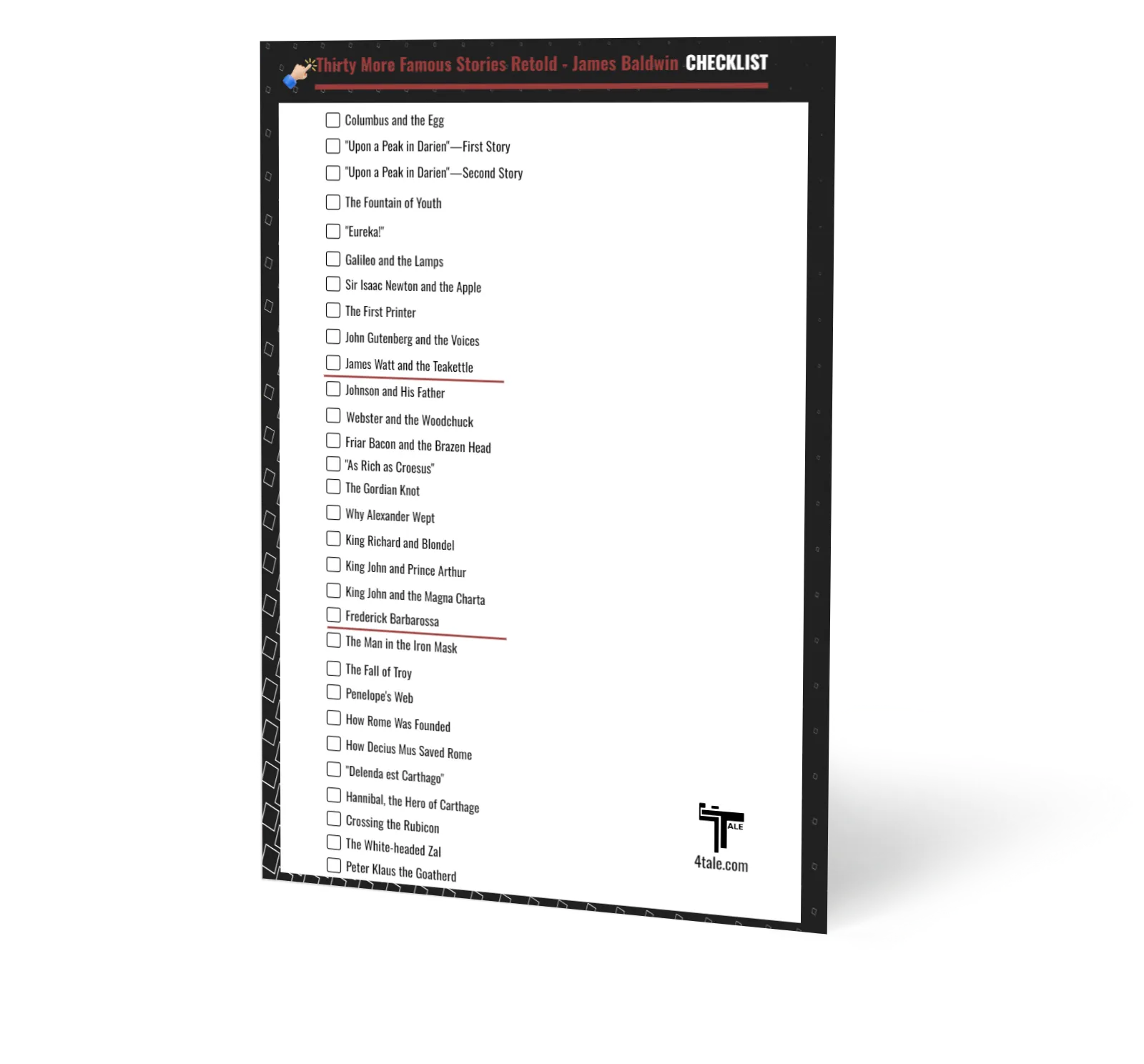

King John and the Magna Charta

Famous Stories Retold: Story 19 of 30

Heading

Significance: The Magna Charta is considered a foundational document in the development of constitutional law, influencing later legal systems and documents such as the U.S. Constitution.

Legacy of Liberty: The Magna Charta’s principles of due process and the rule of law continue to be celebrated as fundamental aspects of democratic governance.

A good book we like, we explorers. That is our best amusement, and our best time killer

- Roald Amundsen, Explorer

Magna Carta: The Foundation of Modern Liberty

The wild tale of King John, a monarch despised for his cruelty and selfishness, whose reign ignited the flame of rebellion among his subjects. This tale of power, tyranny, and the pursuit of liberty unfolds in medieval England, culminating in the signing of the Magna Carta, a beacon of hope for the oppressed. As we delve into this fascinating period of history, we will unravel the intricate threads of political intrigue, resistance, and the human struggle for freedom. A gripping narrative that still resonates today awaits you.

The Reign of King John

The rule of King John is remembered as a reign dominated by avarice and cruelty. His self-centered behavior and ruthless tactics earned him the moniker of Lackland, as he lost one dominion after another that former English kings had held in France. His relentless greed led him to unjustly extort wealth from his subjects, while his contentious nature led to numerous conflicts with his knights and barons. His callous disregard for the rights and feelings of others estranged him from all good men, leading to an isolated and despised monarchy.

King John's Disputes with his Barons

King John's reign was marked by constant disputes with his barons. His plan to wage war against King Philip of France was met with resistance from some of his barons, leading him to resort to violence by burning their castles and destroying their fields. This further antagonized the barons, leading them to convene at St. Edmundsbury to discuss their grievances against the king. Though many were initially reticent, the suggestion of demanding a charter of liberties from the king gradually gained traction, setting the stage for a historical standoff.

Dive Deeper 'Timeless Wisdom' Podcast

Video with Captions and Visualizer

The Role of Archbishop Stephen Langton

Archbishop Stephen Langton played an instrumental role in the challenge against King John. A fervent advocate of liberty, he was present at the meeting at St. Edmundsbury, delivering a rousing speech that emboldened even the most faint-hearted. With his passionate call to action, he urged the barons to stand up against the king's tyranny and demand their rights as free men. His suggestion of creating a charter of liberties that the king would be required to sign marked a turning point in the struggle for justice, igniting a resistance that would change the course of English history.

The Demand for the Magna Carta

In the face of King John's tyrannical rule, the barons of England, led by the courageous Archbishop Stephen Langton, made a bold stand for their rights and liberties. They crafted a list of demands, which would later become the Magna Carta, a testament to their determination to not yield to the king's oppressive regime. The demand for the Magna Carta was not a mere whim or a fleeting thought, rather it was the result of the barons' tireless efforts to secure a fair rule for all Englishmen. It was a call for justice, a plea for the respect of individual rights, and a direct challenge to the tyrannical rule of King John.

The Signing of the Magna Carta at Runnymede

The signing of the Magna Carta at Runnymede was a pivotal moment in the history of England. It was here that King John, pale with anger yet powerless to resist, put his signature on the charter. The Magna Carta, drafted by the Archbishop and his allies, promised to uphold the rights of the people and the cities, and to ensure that justice was neither delayed nor denied to any man. This event marked a significant shift in the balance of power, from the absolute rule of a king to the establishment of a system that recognized and respected the rights and liberties of its subjects.

King John's Death and Legacy

In the aftermath of the signing of the Magna Carta, King John's reign was marred by his attempts to break his promises, leading to war with the barons. His anger and anxiety led to a fatal fever, and he died in a state of disgrace and isolation. His death did not bring forth tears but rather a sense of relief across the kingdom. His legacy, however, is a stark reminder of the perils of unchecked power. Despite his ignominious end, King John's rule led to the birth of the Magna Carta, a symbol of the enduring fight for rights and liberties that continues to inspire generations.

Conclusion

In the crazy tale of King John and the Magna Carta, we've explored the depths of a tyrant's rule, the boldness of rebellious barons, and the enduring power of a document that promised liberty. We've witnessed the pivotal role of Archbishop Stephen Langton in the fight for justice, the unwavering demand for the Magna Carta, and the consequential signing at Runnymede. King John's death marked the end of a tumultuous reign, but the legacy of the Magna Carta lives on as a beacon of hope and a testament to the enduring human struggle for freedom.